Nutritional Value, Addicts, and Berets

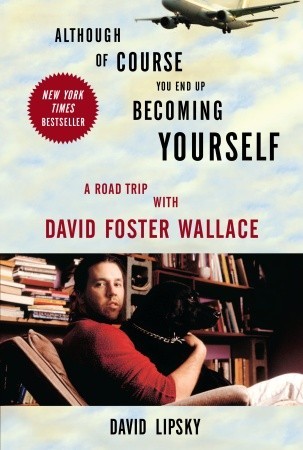

Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace by David Lipsky is, more or less, the collected transcripts of conversations held during the final leg of the Infinite Jest book tour in early March 1996. Though every thought explored during the two authors’ five-day road trip is compelling and worth your time, I’ve focused on the discussions that were about culture, art, and entertainment:

I guess what I’m talking about is entertainment versus art, where the main job of entertainment is to separate you from your cash somehow. I mean that’s really what it is… And I’m not… there’s nothin’ per se wrong with that. And the compensation for that is it delivers value for the cash. It gives you a certain kind of pleasure that I would argue is fairly passive. There’s not a whole lot of thought involved, the thought is often fantasy, like “I am this guy, I’m having this adventure.” And it’s a way to take a vacation from myself for a while. And that’s fine- I think sort of the same way candy is fine. (80)

So I think it’s got something to do with, that we’re just- we’re absolutely dying to give ourselves away to something. To run, to escape, somehow. And there’s some kinds of escape- in sort of Flannery O’Connorish way- that end up, in a twist, making you confront yourself even more. And then there are other kinds that say, “Give me seven dollars, and in return I will make you forget your name is David Wallace, that you have a pimple on your cheek, and that your gas bill is due.”

And that’s fine, in low doses. But there’s something about the machinery of our relationship to it that makes low doses… we don’t stop at low doses.

I’m not saying there’s something sinister or horrible or wrong with entertainment. I’m saying it’s- I’m saying it’s a continuum. And if the book’s [Infinite Jest] about anything, it’s question of why am I watching so much shit? It’s not about the shit; it’s about me. Why am I doing it? And what is so American about what I’m doing? (81)

And so TV is like candy in that it’s more pleasurable and easier than the real food. But it also doesn’t have any of the nourishment of real food. And the thing, what the book is supposed to be about is, What has happened to us, that I’m now willing- and I do this too– that I’m willing to derive enormous amounts of my sense of community and awareness of other people, from television? But I’m not willing to undergo the stress and awkwardness and potential shit of dealing with real people. (85)

…And it’s (consuming junk-media) gonna get easier and easier, and more and more convenient, and more and more pleasurable, to be alone with images on a screen, given to us by people who do not love us but want our money. Which is all right. In low doses, right? But if that’s the basic main staple of your diet, you’re gonna die. In a meaningful way, you’re going to die. (86)

Later elaborates on the “death” caused by consuming only empty-calorie pop culture-

I’m not just talking about drug addicts dying in the street. I’m talking about the number of privileged, highly intelligent, motivated career-track people that I know, from my high school or college, who are, if you look into their eyes, empty and miserable. You know? And who don’t believe in politics, and don’t believe in religion. And believe that civic movements or political activism are either a farce or some way to get power for the people who are in control of it. Or who just… who don’t believe in anything. Who know fantastic reasons not to believe in stuff, and are terrific ironists and pokers of holes. And there’s nothing wrong with that, it’s just, it doesn’t seem to me that there’s just a whole lot else. (160)

Three thoughts (paragraphs) and one question later…

But in a weird way, I think they’re… At some point, at some point I think, this generation’s gonna reach a level of pain, or a level of exhaustion with the standard… you know…. There’s the drug therapy, there’s the sex therapy, there’s the success therapy. You know, if I could just achieve X by age X, then something magical… Y’know? That we’re gonna find out, as all generations do, that it’s not like that. (161)

Is art worth not watching TV for?

Good- I think the good stuff is. But also, I mean art requires you to work. And we’re not equipped to work all the time. And there’s times when, for instance for me, commercial fiction or television is perfectly appropriate. Given the resources I’ve got and what I want to spend. The problem is, when I’m trying to derive all my spiritual and emotional and artistic calories from that stuff, it’s like living on a diet of candy. And I know I’m repeating that over and over. I can find very few analogies that work well. (174)

The paradox is that the popular stuff is training you not to do that work. It’s telling you, you don’t have to do the work. (202)

We sit around and bitch about how TV has ruined the audience for reading- when really all it’s done is given us the really precious gift of making our job harder. You know what I mean? And it seems to me like the harder it is to make a reader feel like it’s worthwhile to read your stuff, the better chance you’ve got of making real art. Because it’s only real art that does that.

You teach the reader that he’s way smarter than he thought he was. I think one of the insidious lessons about TV is the meta-lesson that you’re dumb. This is all you can do. This is easy, and you’re the sort of person who really just wants to sit in a chair and have it easy. When in fact there are parts of us, in a way, that are a lot more ambitious than that… But I think what we need is seriously engaged art, that can teach again that we’re smart. (71)

I have this- here’s this thing where it’s going to sound sappy to you. I have this unbelievably like five-year-old’s belief that art is just absolutely magic.

And that good art can do things that nothing else in the solar system can do. And that the good stuff will survive, and get read, and that in the great winnowing process, the shit will sink and the good stuff will rise. (91)

————————————————————————————————

After I’ve chopped the several conversations down to some of the key points, you can tell that Wallace feels that the majority of the media we consume is cheap and unhealthy. It’s nutrionless candy. He spoke similarly about this when writing about film, excerpted here.

It’s safe to assume that you’ve encountered people who, much like Wallace described, exclusively consume junk-media and may be “dead.”

But what about the other people? The people that present themselves as artists or writers and whose job it is to truly care and create “seriously engaged art”? In the introduction, Lipsky explains that, “As a student, David was put off by the campus-writer look- creamy eyes, sensitive politics. He called them ‘the beret guys. Boy, I remember, one reason I still don’t like to call myself a writer is that I don’t ever want to be mistaken for that type of person.'” (xx)

As a person, David did everything he could to restrain himself and not throw around any condemning labels. But as an author, David Foster Wallce penned the most beautifully harsh descriptions of people and society.

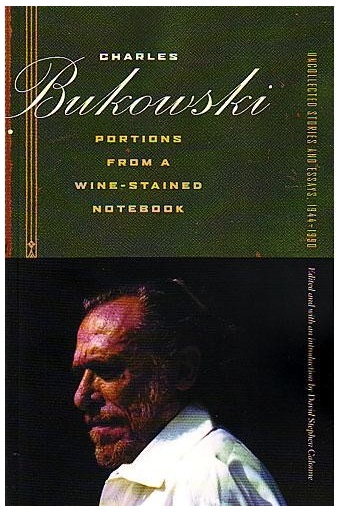

And even though Wallace would probably not appreciate being shouldered alongside with Bukowski, I happened to be jumping between Lipsky’s Although Of Course and Bukowski’s Portions from a Wine-Stained Notebook: Uncollected Stories and Essays, edited by David Stephen Calonne.

Bukowski clearly revelled in his lack of restraint and jumped at the chance to point fingers and throw punches. From Portions:

One time, in my madness, I happend to take a course in Creative Writing at L.A. City College. They were sissies, baby! Simpering, pretty, gutless wonders… They were lonely-hearts and they enjoyed being together; they enjoyed the tight little chatter; they enjoyed their angers and their stale dead unoriginal opinoins. The instructor sat on a hand-knitted rug in the center of the floor, his eyes gazed with stupidity and lifelessness… even when they argued with each other it was still some kind of truce between limited minds. (37)

As well as page 39’s “Can you blame the schoolyard boys for saying that poets are sissies?”

And even prefaced by Calonne in the introdction:

Bukowski’s most intense ire was reserved for the elitist “University boys” who betrayed poetry by playing a safe, neat, clever, professional game of words devoid of inspiration, who tried to domesticate the sacred barbaric Muse: the disruptive, primal, archaic, violent, inchoate forces of the creative unconscious. (xiii)

The issue is this– If the world is chock-full of either lazy consumers of empty-calorie media or sensitive bereted sissies, then what is the best way for “regular**” guys/people who are neither to forge on?

Both Wallace and Bukowski believed that withdrawing from the masses and focusing on what you can control- individual living and writing as the best means.

Wallace:

Give me twenty-four hours alone, and I can be really, really smart.

I’m not all that fast. And I’m really self-conscious. And I get confused easily. When I’m in a room by myself, alone, and have enough time, I can be really really smart. (218)

And one of the reasons why I think when I’m working really hard, that I’m not around people much, isn’t that I don’t have time. It’s just that, it’s more like a machine that you turn on and off. (17)

Because bein’ thirty-four, sitting alone in a room with a piece of paper is what’s real to me. This (points at table, tape, me) is nice, but this is not real. Y’know what I mean? (33)

What writers have is a license and also the freedom to sit- to sit, clench their fists, and make themselves aware of the stuff that we’re mostly aware of only on a certain level. And that if the writer does his job right, what he basically does is remind the reader of how smart the reader is. Is to wake the reader up to stuff that the reader’s been aware of all the time. And it’s not a question of the writer having more capacity than the average person. It’s that the writer is willing I think to cut off, cut himself off from certain stuff, and develop… and just, and think really hard. Which not everybody has the luxury to do. (41)

I’m not sure we’re [writers] any better, but we’re able to describe the attempt to track our wandering circles in a way that perhaps somebody else can identify with. I don’t think writers are any smarter than other people. I think they may be more compelling in their stupidity, or in their confusion. (214)

I think if you dedicate yourself to anything, um, one facet of that is that it makes you very very selfish. And that when you want to work, you’re going to work. And you end up using people. Wanting people around when you want them around, but then sending them away. And you just can’t afford to be that concerned about their feelings. And it’s a fairly serious problem in my life. Because, I mean, I would like to have children. But I also think that the sort of life that I live is a pretty selfish life. And it’s a pretty impulsive life. And you know, I know there’s writers I admire who have children. And I know there’s some way to do it. I worry about it. I don’t know that I want to say anything much more about it– (293)

Buk:

It was best to get the sun on my neck and then dream and doze and try not to think of rent and food and America and responsibility. Whether I was genius or not did not so much concern me as the fact that I simply did not want a part of anything. The animal-drive and energy of my fellow man amazed me: that a man could change tires all day long or drive an ice cream truck or run for Congress or cut into a man’s guts in surgery or murder, this was all beyond me. I did not want to begin. I still don’t. Any day that I could cheat away from this system of living seemed a good victory for me. I drank wine and slept in the parks and starved. Suicide was my biggest weapon. (33)

Being a writer had nothing to do with being anything else. (94)

For some of us the game is certainly not easy for we know the mockery of most funerals and most lives and most ways. We are surrounded by the dead who are in positions of power because in order to obtain this power it is necessary for them to die. The dead are easy to find- they are all about us; the difficulty is finding the living. (41)

Though Wallace was the opposite of Bukowski by making it a point to connect with people and being as amiable and good-natured to everyone- the importance of solitude for both is still apparent.

Other than isolation, there doesn’t seem to be a solution to the problem of each person falling into either junk-media addicts and beret guys. But if you’re ever in a situation where you feel as though you’re surrounded by mind-emptied addicts or pretentious sissies, and you can feel all of your stored humanity draining from you, and your opinions of yourself, those around you and the world-at-large becomes increasingly bleak, this may help:

If you can think of times in your life that you’ve treated people with extraordinary decency and love, and pure uninterested concern, just because they were valuable as human beings. The ability to do that with ourselves. To treat ourselves the way we would treat a really good, precious friend. Or a tiny child of ours that we absolutely loved more than life itself. And I think it’s probably possible to achieve that. I think part of the job we’re here for is to learn how to do it. I know that sounds a little pious.

And because if you think too hard for too long about about this subject, it’s really easy to misplace your sense of humor. Thankfully, King Missile is happy to pull you back to the concrete and locate it for you.

httpv://youtu.be/O-kHB2fWUS8

** Wallace: “It’s true that I want very much- I treasure my regular-guyness. I’ve started to think it’s my biggest asset as a writer.” (42)

May 29th, 2012 at 8:00 am

Loads of things to converse about further, in person, soon. But in the briefest of response for now:

“Both Wallace and Bukowski believed that withdrawing from the masses and focusing on what you can control- individual living and writing as the best means.”

Means for what ends? Because in search of a wholly autonomous life, one that is meaningful in the ways I personally strive, then I think that for me that “individual living and writing” must somehow be connected to others; in consideration of what I hope for US in both sociopolitical and philosophical terms. In other words, while isolation produces an opportunity to do Real. Good. Work., it might also invite an unreflective ego that masturbates on paper all day.

If what fulfills me is to reject the parts of society that I’ve weighed as wrong,

but to still meaningfully participate with those parts, against them, for myself (in consideration of others),

AND I take seriously this withdrawal-from-masses that Wallace & Bukowski are describing,

then I’m interested in what it means to actually “withdraw”, what it looks like to still write Well & Good.

Diggin on thoughts!

xo

September 14th, 2012 at 12:49 am

Yes, thinking too hard about it may cause one to miss the sense of humor embedded there. Great book review by the way.