Film Log #13 – Brando.

I was asked about “top” or “resonant” films. It struck me that I really haven’t written about Brando’s work. Most notably:

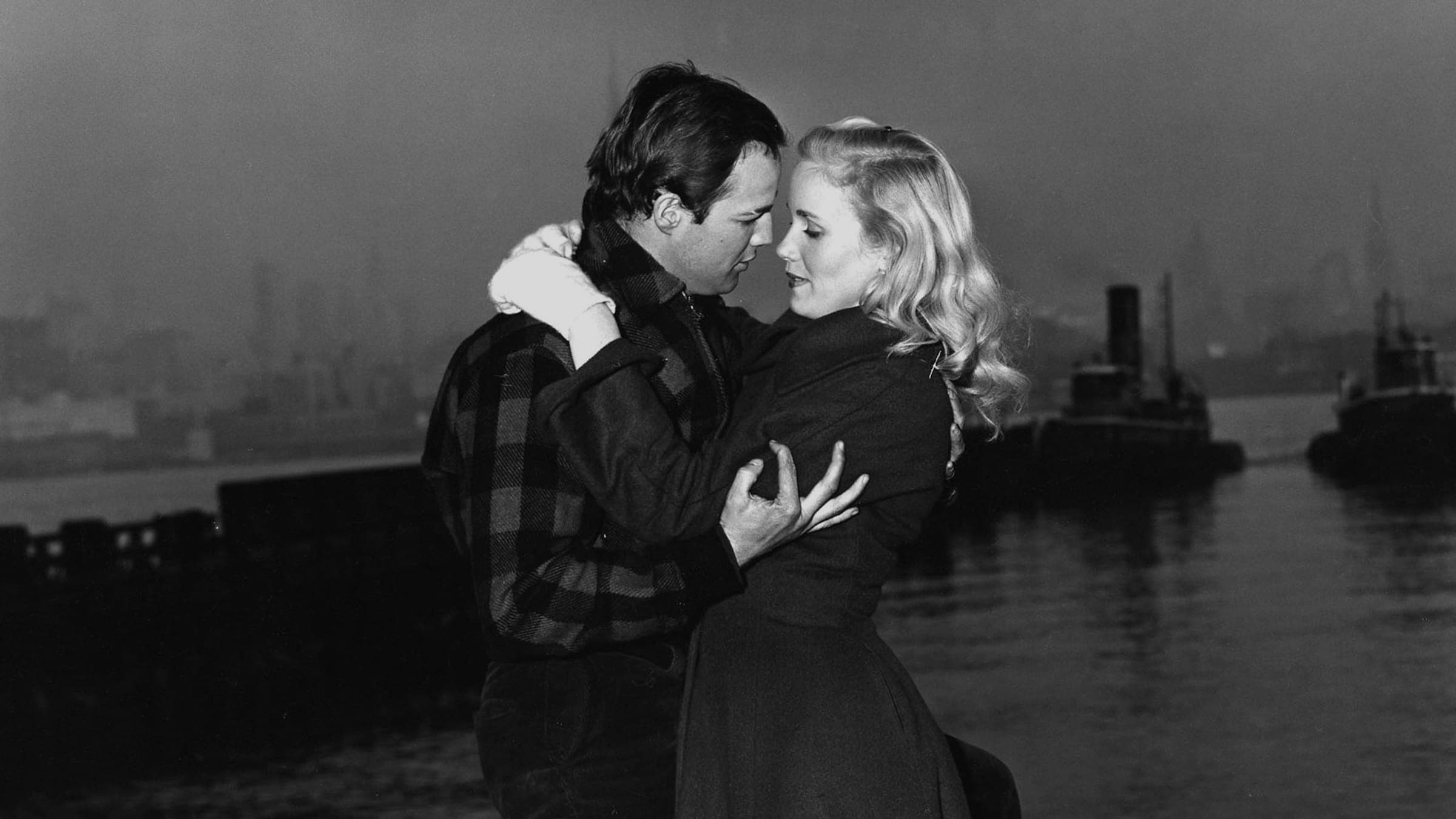

On the Waterfront (1954)

Streetcar Named Desire (1951)

Last Tango in Paris (1972)

Apocalypse Now (1979)

The friend who made the inquiry, Jo Munto, and I agreed to omit obvious choices like Godfather because they’ve been churned into critical mulch by now, and not that the above films are “deep cuts” by any measure, but I’d say most people under the age of 50 have missed them. Which is to say, with the exception of Godfather, most people under 50 have likely missed Brando (crazy).

I’ve recently revisited all of the above films listed (within the past two years or so). An omission I’m unable to write about are the forever-linked films The Wild One (1953) and Rebel Without a Cause (1955). Brando isn’t in the latter, but it’s hard to speak about one without the other and watching both is on my to-do list.

Back to Brando. There are plenty of texts, videos, essays, video essays, about Brando and “method acting.” Most people interpret it as though an actor becomes so comfortable/intimate with their character assignment that the performance becomes paramount. Performance becomes more important than cameras, script, or anything that’s been predetermined.

That’s a very simplistic version of the technique, but with Brando being one of the innovators, it becomes clear that he values being totally comfortable within his assignment that he eventually blends himself into his biggest roles. I would never say that Brando, Nicholson, Daniel Day-Lewis, or anyone who has been labeled as “method” actors, believe their vision is more important than any writer or director, but more that they believe the project is a collaboration and that they should be allowed the opportunity to positively contribute, even slightly alter.

Take for instance Matt Damon recounting this Nicholson story during The Departed.

This isn’t to say that any performance where an actor feels comfortable enough to take pretty big liberties with the scripted character qualifies that performance or technique as “method,” but it is a touchstone indicator where actors began to feel that these characters belonged to them as much as any writer or director.

I’d like to imagine that an understanding writer/producer/director/casting director/etc believes they select talented people who work collaboratively to make the absolute best work of art (I know that’s a simplistic + optimistic viewpoint). And for the times a fan reads that Brando, DD-L, or whoever may have been a “pain” to work with was only experiencing the pains of collaboration. Admittedly, that could totally be white-washing many of these actors’ on-set behavior (primadona or otherwise).

All of this said, On the Waterfront is exceptional. There is the interesting wrinkle that OtW is a response to 1952’s High Noon where Gary Cooper portrays a sherriff who’s compelled by their own sense of duty to face down a gang that is returning to town for retribution. In short, the film is about standing up for “what’s right,” even in times of crisis or danger. Many felt it was an analogy for standing up to the HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) and not naming names.

Conversely, OtW is about Terry Malloy (Brando) who was more or less set up by his brother to do a terrible thing for a crooked syndicate. When the entirety of the situation is made clear to Malloy, he proceeds to cooperate with authorities and reveal what he knows about a predatory, rigged system.

In production, execution, editing, acting, every aspect– both are all-timers; more than worth your time. It’s another example of how masterfully art can present both sides to what one might think is a zero-sum issue, and come away understanding how both perspectives have truth to them. Screening those in succession might lead someone to believe that most issues aren’t boiled down to something as simplistic as “100% right or 100% wrong,” but, depending on any individual’s value spectrums, just to what extent is something more right or more wrong.

I find it difficult to talk about Brando without bringing up On the Waterfront and it’s nearly impossible to bring up OtW without mentioning High Noon.

I’d honestly post links to specific Brando scenes from OtW if I didn’t think it’d somehow ruin the experience of watching the film in its entirety. If you wanna spoil it for yourself, you can find the scenes where Brando flirts with Eva Marie Saint, gives his “I coulda been a contender” speech to his brother, or when he goes toe-to-toe with mob boss Johnny Friendly (played by Lee J. Cobb); or you could screen the movie and enjoy a film that changed acting forever.

I shouldn’t have to spend much time on Streetcar Named Desire. It’s a thing where you either appreciate Tennessee Williams or you don’t. If you haven’t exposed yourself to anything Tennessee Williams, well… you should. Williams’s fiction does tell a particularly monochromatic story, but that doesn’t mean it’s without truth, complexity, or drama.

And what actor brings truth, complexity, and drama to the screen better than Brando?

Nobody.

Brando makes scripted performances feel very much unscripted. It’s not simply little tricks such as talking over another character or being bombastic– he transforms. Like Miles with his trumpet or Hendrix with his Stratocaster, he plays himself into these characters in ways that most successful actors are incapable of doing.

Onto Brando’s Stanley Kowalski–

You know, many act like the concept of “anti-hero” is somewhat new. Nope. It didn’t begin with Walter White or Don Draper or Tony Soprano or any 90210 cast member or Don Corleone or any representation of Scarface or Kerouac’s Dean Moriarty or any of James Cagney’s characters or Twain’s Huckleberry Finn or any American character for that matter.

I know there are centuries between these artists, but we can look to Homer, Cervantes, and Shakespeare and find many antiheroes.

That said, it’s near impossible to be as simultaneously magnetic and repellent as Brando is as Kowalski.

He’s selfish, brooding, cocksure, stubborn, and doesn’t have time for all the bullshit that his wife’s sister, Blanche (played by Vivien Leigh), injects into his home. As mentioned by his repellent nature, Kowalski handles Blanche’s extended visit despicably, but, pardon the cliche, it’s a car crash we can’t look away from.

SND is perfectly crafted storytelling by Tennessee Williams that’s masterfully executed by Brando and cast. If that doesn’t compel one to watch the movie, I’m not sure what will.

Brando, who had fought to be anti-authority in the 1950s had seemed to lose that battle much to his own personal troubles and succumbed to regarding acting/Hollywood as just a job to pay the bills and he subsequently became a working stiff unable to inspire the public.

So strange for a man who had such a hand in building a counterculture in one generation to be regarded as a lousy, two-bit, over-the-hill companyman by the next.

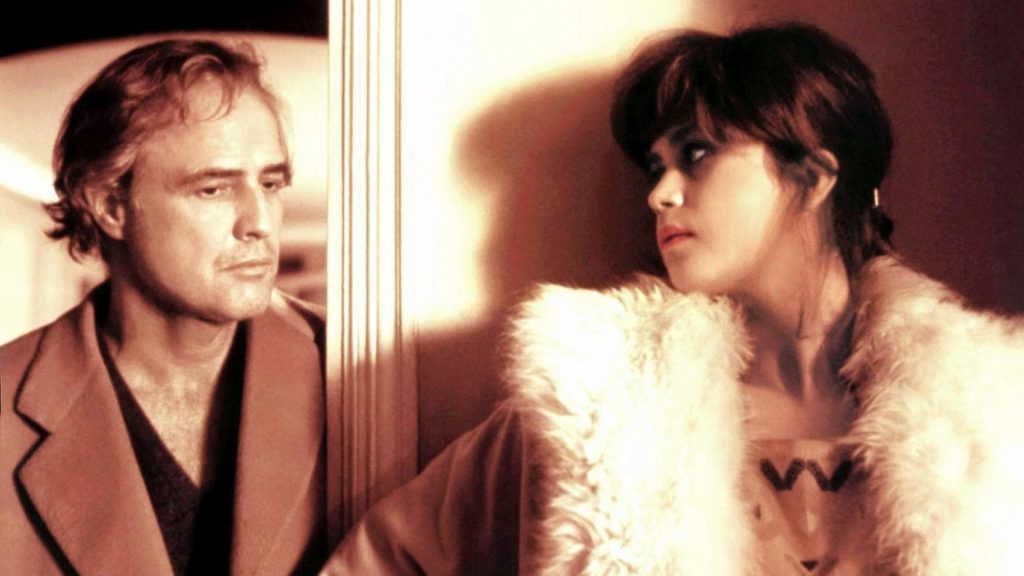

Luckily, Francis Ford Coppola came calling and offered Brando the Godfather role provided he didn’t thwart production as he unfortunately had done during a few projects in the 1960s. Brando’s Godfather experience, more or less, reignited something in him where he felt motivated to work on an experimental project with Bernardo Bertolucci– Last Tango in Paris.

The film isn’t without bad press, was scandalizing at the time, and has only aged poorly. The main reason people find it distasteful is that both the lead actor and director manipulated the young, impressionable lead actress, Maria Schneider, into participating in simulated acts that weren’t scripted. Most notably, a rape scene.

These aren’t the scenes that I’m thrilled by. What does intrigue me are the scenes where Brando injects his personal childhood experiences into the Paul character, a monologue beside a corpse, and a scene between Brando’s character (Paul) and Paul’s wife’s extramarital boyfriend.

The film is also a lesson in desire and how sometimes passion wanes once advances are not just accepted, but wholly embraced. The immature, but all too common belief that the “chase is more thrilling than the actual prize.” Clearly, it’s a complicated film, but interesting nonetheless.

I understand the film’s criticisms range from outrage to advanced concern, and those criticisms may outweigh some incredible scenes, but those incredible scenes do still exist.

For as sprawling and spiraling as Apocalypse Now‘s narrative is, the film anchors on Brando’s performance as Colonel Kurtz. It’s a long film that winds its way for 90 minutes as Martin Sheen tells us about this mysterious Kurtz. Then Brando shows up and surpasses everything we could’ve presumed.

It’s incredible.

Again, I would link clips to specific scenes, but they’d either spoil the plot or would take the air out of your experience if you haven’t seen it.

YouTube some scenes if you like, but I believe you’d be much better off giving this film 150 minutes of your time.