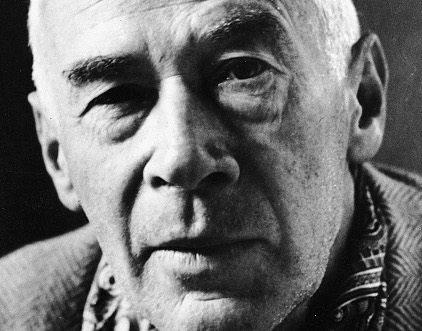

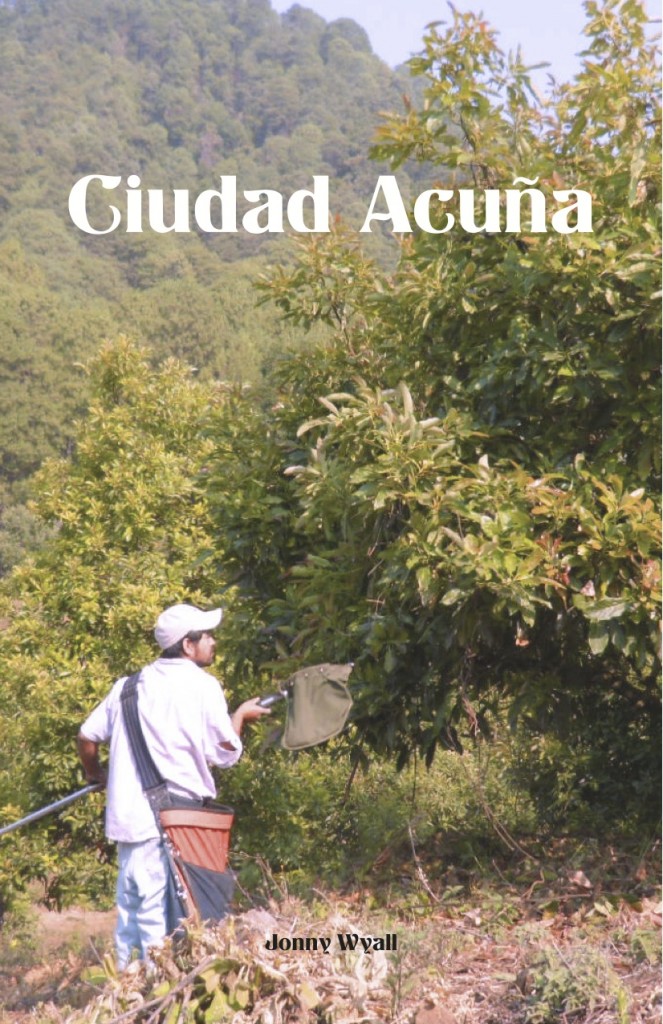

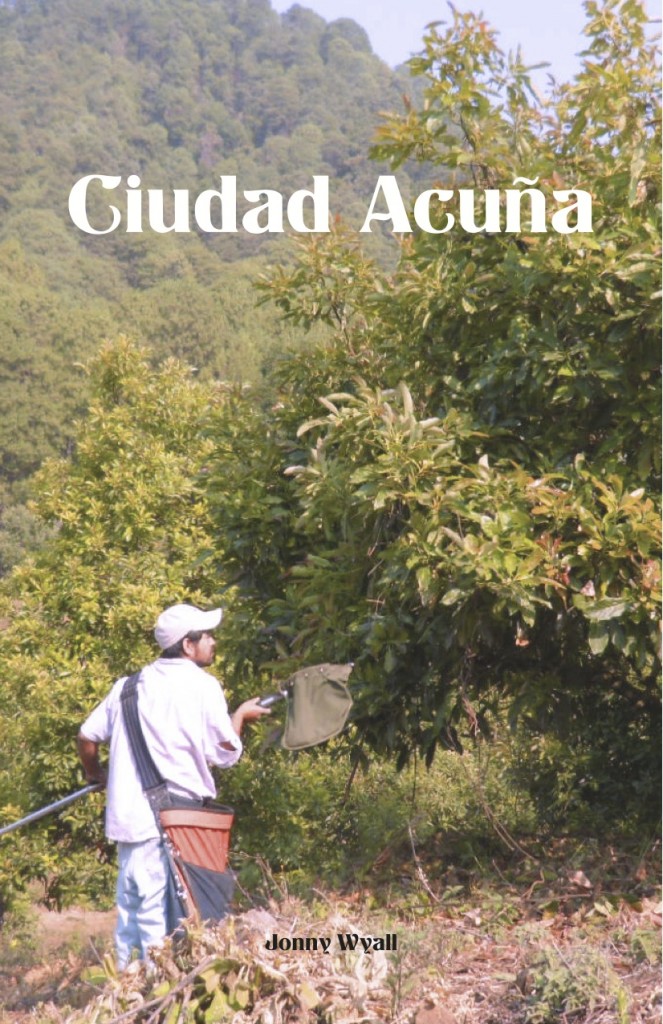

The latest from Jonny Wyall –

Marisol moved out to her father’s avocado orchard the summer of her eighteenth year. She told her mother that it was a matter of establishing Californian residency so that she might be able to afford the likes of a prestigious state institution when in fact she had no mind to enroll anywhere at all. She only wanted to be with her beloved Umberto Colerto who was working full time on the same orchard.

Now Umberto Colerto was three years Marisol’s senior, a fine avocado picker, a better wheel-man and, above all the sun-ripened fruit of a generation’s labor. He was a pocho, California via Texas via Coahuila. His parents were Mexicans and had been in and out of deportation bureaus – a humiliation Umberto would never have to know.

“You’re an American, mijo.” Señora Colerto told her baby boy. “Someday that’ll be worth something.”

And, of course Señora Colerto was right. Upon turning seventeen Umberto promptly dropped out of high school and picked up a job with Coca-Cola. By eighteen, he was promoted to delivery driver. He loved being on the road and the work paid well. His feet knew the gears of his transmission like his tongue knew the taste of the tamarind fruit. He was even friendly with the clerks he delivered to, clerks like Señor Longoria at the Diamond Shamrock.

“Que onda, Umberto?”

“Hey Mr. Longoria. Got some Cokes for you sir.”

“Not for this diabetic.”

“You have to get off the cookies, sir. Nothing better than a Coke, a little ice, maybe a lime.”

“Sure, and you gotta get out of that uniform and chase some women, Umberto.”

Umberto had stocked that Diamond Shamrock a hundred times before but surprises always seem to hide deep in the ledgers of repetition. He was on his way past the register with his second dolly-full of Cokes when he noticed that something pretty had been flushed out of the urban undergrowth and chose to alight by the fridges.

Longoria had seen it too. “Suerte, compa,” he winked.

Umberto approached with caution just as the thing reached for a Coke off the front row. He had to say something.

“Excuse me, mam.”

It pulled back immediately. Flight was imminent.

“You don’t want one of those up front. Here, let me get you–”

“Mam?”

“Well, those are a little warm. I’ve got some cold–”

“Doesn’t it make sense to assume the best in the strangers you meet?”

“I was just assuming that you wouldn’t want a warm Coke, that’s all.”

“Well… I don’t.”

“Good, because you know mam, a warm Coke goes flatter quicker, the bubbles burn the tongue, it’s not nice.”

“I’m a Ms, Ok?”

“Looks like I’m amiss,” said Umberto. “But I can’t let you take a warm Coke. Here–”

He reached to the back of the fridge then stopped. “You know what? I’ve got something better out in the truck.”

Umberto motioned and the girl followed him out to the last chamber of the Coke truck. He lifted the door, and took out an old, worn bottle.

“It’s a Mexican Coke. Some stuff’s better from Mexico.

“Thanks.”

“Sure.

“Well sir–”

“It’s Umberto. Umberto Colerto.”

“Well Umberto, I’m out of gas.”

“It was either that or you’ve got a sniffin’ problem.” He certainly rounded off his b’s like a pocho.

“So… I–”

“So go get your the little can filled up and I’ll give you a ride to your car.”

“You don’t even know my name,” she said.

“We’ll get there.”

And get there they did. It started with 12 ounces of Mexican Coke and grew into a 12 month courtship. They danced the old dance – they drove around all weekend together with nowhere to go, then Monday night Umberto called and they talked about nothing and eventually all of the nothingness added up to a knotted pile of somethingness poised to clarify itself on the eve Marisol’s graduation.

Marisol still hadn’t committed to a school. Anywhere she went would take her away from Umberto. Anywhere she didn’t go would become a door locked forever. She cried in Umberto’s arms.

“I don’t know what to do.”

Umberto cradled her like a baby. He needed a woman. Why: he couldn’t be sure. He felt close to his ancestors when he played the comforter. He closed his eyes and rocked his woman the same way his aunt had rocked him when his father had abandoned him in Texas.

“I know it hurts baby,” she said. “Seven’s much too tender.”

He thought about the trip to Lake Amistad. Tio Colerto drove just the two of them down to Del Rio. They had lunch at a cafeteria – ate chicken, drank ice tea – and when they finished Tio Colerto brought over a piece of cheese cake with two candles stuck in it.

“Eleven’s a good age for a boy,” he said. “Still has heart.”

They never made it up to Lake Amistad. Instead, after the meal, they crossed the border to Acuña. Umberto remembered how bad his mother’s house looked, one wall completely collapsed, rebar hanging out of the second story floor. A litter of street pups nursing in the corner, the after birth still wet on their tiny coats. The chicken in Umberto’s belly turned over.

Señora Colerto and her whole flock of friends were all there cooing over how big the baby boy had gotten. They were fat women with stringy hair, mostly barefoot. They stunk of sweat and dog. Umberto’s mother cried – some for the years she’d missed, some for the whore she turned into.

Umberto’s dad and uncle embraced later at the cafe. They spoke in hushed, colloquial Spanish about the details of the boy’s future. The waiter brought three Corona’s and a Coke; a special occasion indeed.

The streets were dirt and full of trash. The people were often kind and happy but seeing those smiles amidst the squalor was unsettling and Umberto didn’t like the position it put him in.

“Acuña’s a shambles,” Umberto thought.

The only chance anyone had was to leave; no one knew this better than Señor Colerto, twelve years banished. To return brought grief and regret. Grief over the good lives rotting away there. Regret for one’s own impotency in reformation. Señor Colerto worked for eight dollars a day in the maquiadoras, the American assembly factories set up around Acuña. They paid only six for those in need of factory housing.

All of this Umberto kept from Marisol that he might console her. His past reminded him to distinguish true tribulation from an untimely hiccup in the twisting bowels of the first world. Marisol had never known national displacement nor did Umberto ever intend on showing her, at least not at first. But the moonlight began to have its way with his good sense and when Marisol was done crying they came together on the blue couch at her place.

The next morning they walked down to the community pool: Umberto Marisol and her little brother Pudonte. Umberto paid everyone’s two dollars and they were in. Marisol swam off leaving Pudonte and Umberto alone on the pool chairs. Pudonte was a puny boy, the product of a working mother and an absentee-avocado-farming father. If greatness breeds greatness, one can only assume the reproductive tendencies of mediocrity.

“See that kid over there,” Pudonte said.

Umberto peered out from under the towel covering his face.

“That kid, Daniel Rosenbaum. See him?”

“What about him?”

“That kid’s got it coming. Last week he squealed on our hook up.”

Umberto sat up. “You’re pushing product already?”

“Cherry magazines,” Pudonte clarified. “Epiphanio was selling them out of his locker. His dad’s got so many. Epi swipes ’em all the time.”

The kid was splashing around and shrieking like an idiot.

“But Rosenbaum got caught, see. He led the principal right back to Epi. They got some kind of school warrant, popped his locker open and found the whole stash.”

“You gotta keep your friends close, P.” Umberto put the towel back on his face. “And the Rosenbaums of this world closer.”

Umberto remembered why he dropped out of high school. He did feel a sort of fraternal allegiance to Pudonte even if he couldn’t show it. The times were good; the sun was shining, his girl was happy – but even through the towel Umberto could smell the faintest of scents, the turning of summer’s sweet freedoms into the urgencies of fall.

If he wanted to foster this good thing he had out of its infancy he’d need his best wit. Now that there were more people on board the boat needed steering. No one had told him to savor his time wayfaring and in the wake of its passing he held tight to what he could remember of it. After all, those memories are the opiates that ease one into celibacy.

Marisol swam up to the ledge of the pool. “Come on boys, let’s get wet,” She said.

Pudonte jumped in with all his clothes on.

The next day Umberto was out delivering to some of the peripheral convenience stores. It had been a fine day; of no particular note other than it would be Umberto’s last. He turned off into a neighborhood and down shifted to a third gear idle. Coke had been good to him.

There was a cross breeze blowing through his open windows. The mailboxes ticked past. Painted wood posts, beveled stone, brick – they were all miniatures of their corresponding estates, all meticulously modeled in the lot’s theme. He slowed in approach to the white stone of #204. The Rosenbaums.

A man pranced through the yard wearing flowing sleeves and a dumpy sun hat- Rosenbaum senior. He bent over and snipped a shoot off his pomegranates. Umberto headed for the cul-de-sac and turned his truck around squaring up to the house. “It’s a good way to go out,” he thought.

Rosenbaum snipped off another shoot from his pomegranates and looked up just in time to see a Coke truck coming right at him. The engine backfired, Rosenbaum dove into the bushes, the Coke truck jumped the curb and razed the Rosenbaum’s mailbox. The crowd cheered. They come to the corrida to be entertained. Rosenbaum peeked over the bushes, his his face bleeding where he’d caught a shard, the Coke truck idled atop the razed edifice. Rosenbaum scrambled to get the tags. The crowd booed. They believed the truck showed great heart and should be spared.

This was the Rosenbaum’s residence, but after the mailbox incident it was clear whose house this was. Umberto lowered his hat. The truck lurched into gear, rolled over the rubble and out into the free world.

Of course Rosenbaum reported the incident. Umberto offered Coke no explanation and was fired. But the smugly satisfied look on Umberto’s face, the half-cocked smile through his chewing of a peanut butter cracker during the reprimand spoke to the liberation of his termination.

Marisol was scared, what would come of this? Maybe she could work, put off college for awhile and move in to Umberto’s place with him…

“No,” Umberto told her. “We’re not getting stuck here.”

“But it’s nice–”

“They don’t need us here, baby.”

And with that Umberto packed up his truck – a sleeping bag, a pillow, and a cooler from which he procured an avocado. He tossed the avocado between his hands as if acquainting himself with it.

“It’s what my dad used to pick,” Umberto said. “That’s how we made it for a while.” He put the avocado back in the cooler. “And that’s how you and I will make it too.”

“Goodbye Umberto,” said Pudonte. They slapped hands then hugged.

“Be a good boy, P.” Umberto told him. “Oh, hey, wait.” Umberto opened the door reached behind the seat and pulled out a fresh Cherry magazine. “This ought to get you guys back up and running.”

“And for you,” Umberto turned to Marisol with an envelope that had her name on it. “I’ll see you in 3 months.”

Marisol took the envelope and hugged Umberto. “That’s a long time” she said. “What if something changes?”

“Somethings take a long time,” he said.

“I could just come with you now,” she said.

“I’m gonna have to get the work on my own terms.”

“But what if my dad doesn’t hire you?”

“Well then he’s gonna wish he did when I’m picking twice as fast as his guys but for somebody else.”

Umberto started his truck and drove off.

That night Marisol sat down at her desk and opened the envelope. Along with plane tickets to San Diego, there was a letter.

“Dearest Marisol, there are some things you have to know about where we are going before you decide to leave where you are. Ciudad Acuña is at once the foulest, desperate places I know, yet it beckons.

“There was love, I’ve been told, and even a little money on occasion but the times were mostly hard. My dad labored in the U.S. when he could get in. He’d be gone sometimes six months when the work was good. He was a picker, gentle with the fruit, efficient, strong-willed. My mother would wait months for him to come home. Then one day there’d be two tiny trucks on the horizon, one towing the other. I wasn’t even born yet but my cousin Rojillio would run out to the street yelling, “Tio, Tio!” hoping that hidden somewhere in those trucks was a new soccer ball. My dad would look up from tickling him and my mom would be standing there, nearly in tears. They would embrace and for a moment the family would be happy.

“But the money never lasted long and the times would get hard again. There would be fighting, my dad would drink harder and harder until there was nothing left and he would have to leave again. Most of the men in Acuña operated like this.

“There were a few restaurants, a small flea-market selling chucheria to the border traffic, a lavanderia, and even a club. These places could hardly provide a living wage to the few workers they did employ, most of whom were children. That’s all Acuña ever was – women and children. The women would chatter like little birds washing clothes, providing support for each other when a husband had been gone too long or when a boy had become old enough to leave for work in the U.S. There were many tears to be cried over such occasions.

“My mom always kept a steady hustle, though. She collected Coke bottles, mended dresses and, though she’d never meant to, she even took some night calls when she had to. Together with my aunt they made it work for a while.

“Then one day my dad came home with very little money. He’d overstayed his green card and it’d cost him everything he’d earned in deportation expenses. He was banished to his own country. He took to drink and became even more demanding of my Mom. He’d yell when she’d leave to work at night and by the time she’d get back he’d have passed out somewhere in the dark house. She’d step lightly, sometimes to discover a puddle of vomit here or a pool of urine there. My parents didn’t have a shower to wash themselves, no running water to clean the messes, no railings by which they could pull themselves out of the filth.

“It wasn’t long after Dad got home for the last time that I was conceived. Biologically, it didn’t matter from whom I came; I was called Colerto.

“I gave my Mom hope. She loved daydreaming of the places she’d take me, the things she’d teach me, (I could only be a boy, she was sure). But as my due date approached my Mom realized what a Mexican birth would mean for my future. Dad had been a good man and look what Acuña did to him. So Mom cried one lonely tear for her mate, a tear that rolled down her nose and dropped into her Topo Chico, then she got to work.

“She decided to hire a coyote to take her across the border up to San Antonio. Everyone knew someone who knew a guy in Acuña and it wasn’t long until she’d talked her way into the acquaintance of a coyote called Beto, whom she agreed to pay $300 for the trip.

“Beto had had some success with a few families in Acuña but perhaps it had been a thing of luck. He was reckless and forgetful. He twice missed the rendezvous while this Señora Colerto, whom he hardly knew and cared even less for, shivered on the banks of the Rio Bravo. She’d wait a few hours then slip back into the water and over to the Anglo side again.

“I was kicking then, ready to pop out and get to it. Mom hushed me with a rub of her hand while the other combed out her smooth black hair. She set off for the river one last time.

“It was a three mile walk south to the spot where the fence was snipped. She pulled back the rusted chain link, ducked through and then repositioned it so that it would stay unnoticed in case her sister ever needed the route. She waddled down to the banks, took off her sandals and tucked those into the trash bag she’d brought along for her dry things – her serape and some white pieces of sheet – just in case I came early. She tied off the bag, smeared mud on her face and arms, and waded across the Bravo.

“It was 1:15 when Beto’s truck finally showed up. ‘Buenos noches, Señora.’ He said. He lifted his night-vision and produced a red pocket light with which he lit the way. ‘Vamos.’

“He loaded us into a fake tool box buried in blankets and covered with a camper shell. He kept the truck blacked out, using his night-vision to navigate a system of ranch roads, stopping often to open and close galvanized gates.

“Each time they stopped my mom would fear the worst. Then she’d hear a gate creak open, the cattle guard buzz under their tires and they’d be back on their way. Though she needed it, there was no sleep to be had in that box. She felt contractions coming on. I was ready.

“She kicked open the little door she was hidden behind, did her best to spread a blanket. Green and red lights flashed on behind them. Beto sped up. My mom screamed. The contractions got stronger, longer. Beto lost control, spun off the road and slammed into a ditch. He took off. The back doors flung open and there stood two U.S. Agents, official witnesses to my American birth.”

Marisol realized her place in the entitled generation. Even if she did get pregnant it would be nothing like what she’d just read. Things were easy for her and thusly she felt yoked with a weighty debt; how much and to whom was unclear. She read on.

“My mom was arrested and we were deported as soon as my umbilical cord had been cut. My dad met us at the border. He stayed awake for a very long time after that. I was dealt an ace.

“I spent the next seven years in Acuña. My dad was working again, this time for the hotels down in Playa del Carmen. The money wasn’t as good as it had been picking, but at least it was steady. My mom still washed clothes and worked around the city to make ends meet. When I asked her about those days she told me I had a cat that I loved very much and there’s even a picture of me holding it but I don’t remember loving any cat.

“One day my dad told me to pack a bag. ‘We’re going to see your Tio in Tejas,’ he said.

“My uncle’s place wasn’t much to look at but there was a lot of land to play on and there would be American schools and American standards. We stayed in Texas for a week until all the arrangements had been made between the men. Dad bent down and hugged me. ‘I’m going to rent us a few movies,’ He told me. Then he kissed me and drove off.

“I cried a mighty cry when I found out he wasn’t coming back. But the tears dried on their own. ‘Crying won’t get it done,’ my uncle told me.

“Ever since I moved to Texas I dreamed of going back to Acuña, raising my family, starting a business, hiring on a few hands. Everyone says America is the land of opportunity and, true enough, it still fosters the opportunistic, but sloth reigns. Those guys down there in Acuña need what we’ve got more than anyone here does.

“Come to California with me, Marisol. From there we’ll set it all in motion. Love, Umberto.” Marisol cherished the letter.

***

It was the last day of picking for the week, and soon enough, the season. Eugene made his rounds through his orchard like he did every day. He started with the machine shed, checked the truck’s tires, made sure his guys swept the place out the night before. Everything was well arranged so he moved on to where the pickers were picking.

The avocado crop was average that season, but the trees were still young and there was plenty of improvement Eugene could prune into those trees in the coming winter months. Young trees can’t be expected to bear with such austere solidarity with the single-minded dedication to production of older stock. There was still time.

Most of Eugene’s pickers were of that older stock. They’d been around long enough to know what Eugene expected of them including, with reasonable allowance, the expectation that all pickers respond to English. The result was a lean business: five pickers, two barns, one truck. There was housing for the pickers and everyone ate breakfast and lunch together in the big house. In the end, Eugene was able to coax enough fruit out of his trees to keep bacon on the table.

Umberto was the newest picker but, like the rest of the Colertos, he worked with passion. He learned the Californian clipping process fast, filled his fruit bags with fervor and struggled only when it came time to finish the tops of his trees with a picking pole. He took delicate pride in handling the avocados and even the other pickers noticed the sentiment. There was no greater variety than the Haas they harvested, nor a greater region in which to grow it.

“Umberto come down here, I’ve got to talk to you.” It was Eugene. He’d nearly finished his rounds and come upon Umberto still working in his tree.

“Yes sir, boss,” Umberto said. He swung down and followed Eugene to the truck. “Nice day, huh boss?”

“Sit down, Umberto.” Eugene said.

“Yes sir.” Umberto took a seat on the lowered tailgate.

“Umberto I like you, you do good work around here.” He spoke with unease.

“Thanks boss.”

“What I mean to say is, I don’t want to lose you to the off-season. I know how you guys are – you work, you move on. I understand that. These guys just load their entire lives into these tiny shit Nissan trucks, hook ’em together and I never see ’em again.”

“Well it saves on gas that way, boss.”

“I know it does,” Eugene said, almost sentimentally. “But you don’t have one of those little trucks, Umberto.”

“No sir, I’ve got a full-size.”

“Look, I know it’s only been a few months, but I can tell by the cut of your jib that you’re not like those other guys.”

Umberto now knew where this was going and he took a deep breath, wished the clouds would open up and start raining, spare him from doing what diligence demanded.

“I want you back next season, Umberto. That’s why I’m going to double your price. You’ll be picking twice your weight by then anyway and I think you’ve got a good way with the other guys.” Eugene was proud of himself, like he’d been rehearsing. “Well, how does that sound?”

Umberto looked pale.

“Well come on then, it’s twice what you could make at any other farm.” He reached into the sack he’d been carrying, procured two Diet Cokes, still cold, and handed one to Umberto.

“Thanks boss,” Umberto said. “Listen, there’s something I gotta tell you.”

“If it’s about that magazine that disappeared off the john–”

“You know, somebody got your daughter pregnant.” He paused. “And what I’m trying to say here is I got your daughter pregnant.” Umberto was hit with a flood of emotion. All the passion he shared with Marisol suddenly stood trial. “We’ve been together for a year, since Texas boss, I swear. It just happened, you know.”

“What happened?”

“Well, we just got back from Sonic, you were out… so we took your bed–”

“What I mean is… why couldn’t you guys tell me?”

The two sat in silence a moment, both holding their Diet Cokes.

“I came out here because of her, boss. To ask you for her hand. It’s what we both want.”

“I’m gonna be a grandfather.”

“That’s right.” Umberto smiled. The labor had disposed him to enjoying simpler things. “But I can’t come back next season, boss.” I’ve got to go back to Acuña. I have to take your daughter there and raise my family. I can’t come back next season– I’m sorry boss.”

Eugene looked over his orchard. It was what he knew, it was his work. How could one man deny another his work? He twisted off the cap to his Diet Coke, raised it in a cheers and said, “To Acuña.”

Umberto laughed. “To Ciudad Acuña, boss.”

They both had a long drink and even though the picker would have never picked Diet, it still tasted good.